In loving memory of Michael Pasken.

On December 18, 1980 I found myself on a flight from Thailand to Columbo, Sri Lanka. It was a surprise to me as I had arrived in Bangkok just that morning. I had been expecting to meet up with Michael and Phil and backpack through Thailand for the winter. However, my adventure-seeking friends had found Thailand too tame for their liking and had changed our plans. So here I was, heading to the Indian subcontinent with zero knowledge, planning, or research about my destination. Although I had previously spent a year living in Europe, I was pretty naive, I had no idea what I was getting into. I had my orange backpack, $600 in travellers checks, an open mind, and a hopeful heart.

The backpacking culture which emerged from the bohemian 50s and the hippies in the 60s and 70s had created a new breed of nomads, vagrants, beachbums, outlaws, mystics, hedonists, stoners, explorers, and searchers who wandered the world wanting to disappear or to find themselves. I was initiated into this motley crew of international travellers that day. I had found my clan.

Travelling was a true adventure then, there were few guidebooks and information was shared through conversation over a beer or cup of tea, or posted on the ubiquitous bulletin boards at back packers’ hotels and eateries on the global hippy highway. Post restante and American Express offices were another important source of communication. Letters home could be posted or retrieved. Messages from friends could be found or left in a box on the counter, and attempts at international phone calls could be made, often lasting all day with disappointing results.

We all carried tattered maps and journals filled with notes and hand-drawn maps and business cards gleaned from other travellers. We often didn’t know exactly where we were going, how we were going to get there, or what we would find when we arrived. It was challenging, exciting, often uncomfortable, sometimes dangerous, and we learned something new every day.

Sri Lanka

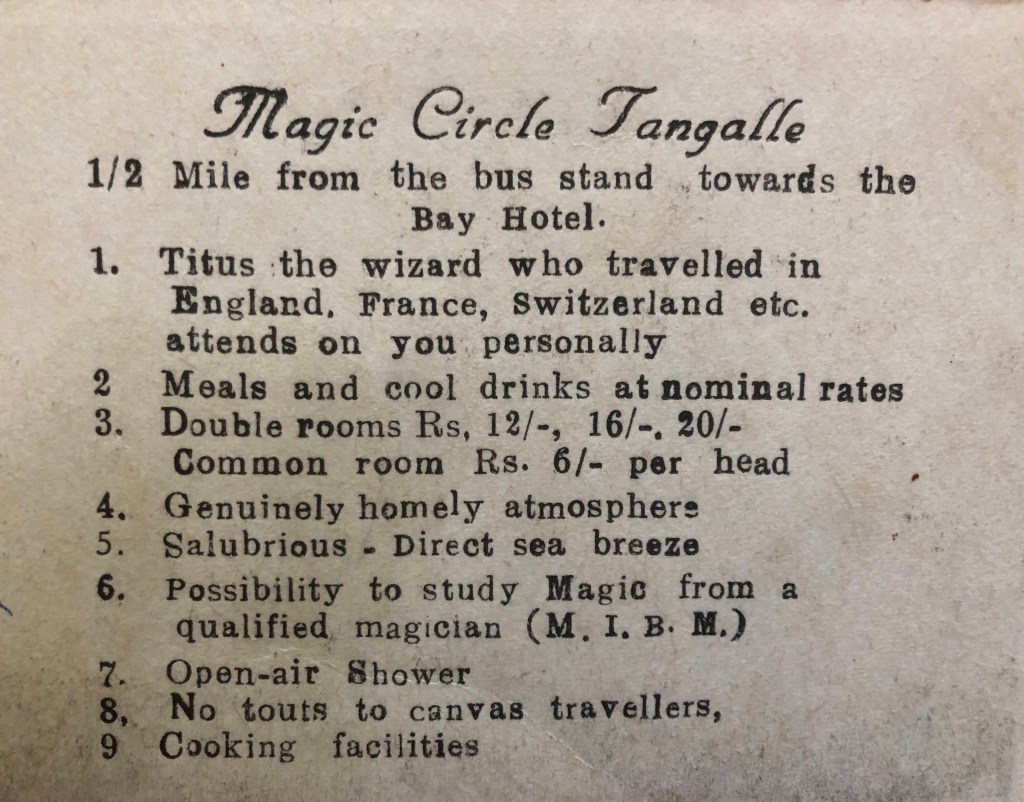

In the village of Hikkaduwa on a wide Pacific beach lined with impossibly narrow fishing boats and towering palm trees we celebrated Christmas and played on the beach which we shared with fishermen, surfers, and sea turtles. We spent the next few weeks exploring the southern part of this bright green jewel of an island. Our travels took us to Tangalle and the Magic Circle, a guesthouse run by our kind host the one and only Titus the Wizard. Our days were spent playing in the surf on the pristine beach or playing cards in the “genuinely homely atmosphere” of the Magic Circle, refreshed with tea and a “salubrious sea breeze”. From a rickety bridge we watched six-foot lizards devour a dog in the river. We followed huge butterflies down jungle paths that led nowhere. After a tropical downpour the roads became impassable for cars and we bounced around on the back of an oxcart. We became immersed in this bizarre world, the people we encountered were as surreal and surprising as the flora and fauna of the surrounding jungle and ocean.

Michael’s health had started to deteriorate. At an overcrowded hospital in Columbo he was diagnosed with hepatitis. We made our way to Kandy, the capital city in the mountainous interior, where we installed a yellow and gaunt Michael in a sanitized private clinic run by Jehovah’s Witness’. A wonderful family who owned the guest house we stayed in had befriended Michael and promised to look after him while he recovered, so Phil and I carried on, hoping to meet up with Michael down the road.

India

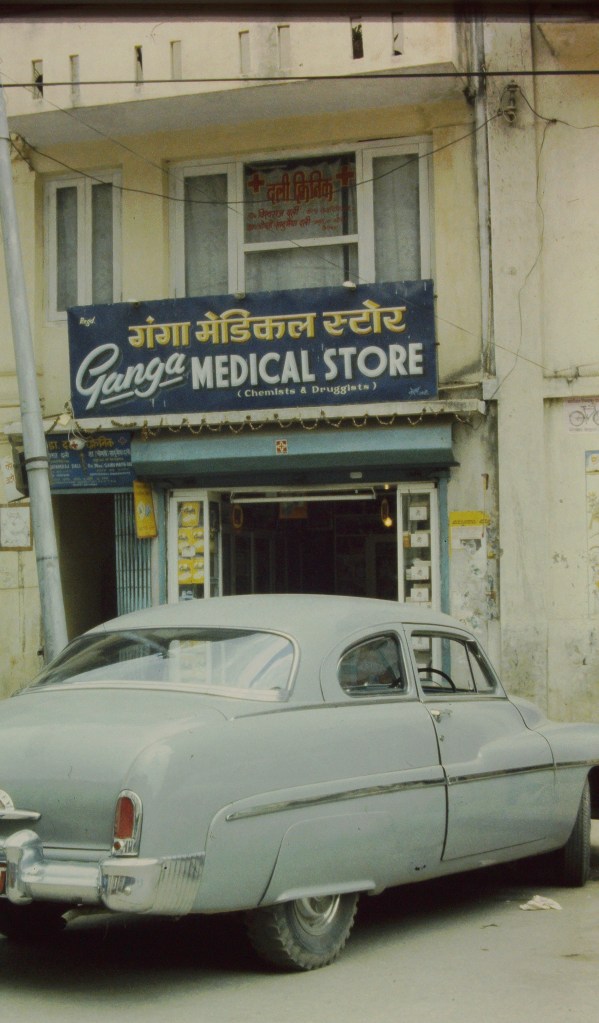

Our travels in relatively clean, calm, green pre-civil war Sri Lanka did not prepare us for the churning chaos that is India. The smell of decay and shit and incense and flowers, the holy men with their loincloths, dreds and begging bowls. People with broken bodies or minds, reaching hands and pleading eyes. Crumbling Victorian mansions with trim lawns and exquisite architectural monuments to the gods and goddesses of the many faiths practiced here. Fat bejewelled families perched on rickshaws, pulled by skinny loin-clothed men with opium glazed eyes. Roads snarled with old model American cars, ox carts, bicycles, motor bikes and tuk tuks, often brought to a standstill by a recumbent cow, calmly chewing its cud in the middle of the road. Greasy guys in tight western clothes and wraparound sunglasses, women draped in bright saris with gold on their wrists and dripping from their ears and nose. The volume of people conceiving, birthing, cooking, eating, shitting, worshipping, living, and dying on the streets was astounding.

India is a country of extremes, it can provoke feelings of love, anger, awe, frustration, distress and hilarity, sometimes all in one day, or one hour. The challenges of communication, the pointless paper pushing, the endless festivals and curious customs made every day a bizarre experience. That ambiguous head roll and smile that is the mysterious answer to every question. Purchasing a train ticket or cashing a travellers check could easily turn into an all day affair. Worship is part of everyday life, not confined to temples or special days, religious processions and celebrations could fill the streets and block traffic for days. Street vendors were forever shooing away the urban monkeys and spoiled sacred cows trying to help themselves to a meal. There is no concept of personal space in India. People would often sit close to me and stare, sometimes reaching out to touch my blonde hair and pale skin. It was harmless but unnerving. Endless patience, a sense of humour and an appreciation of the absurd is essential for surviving India.

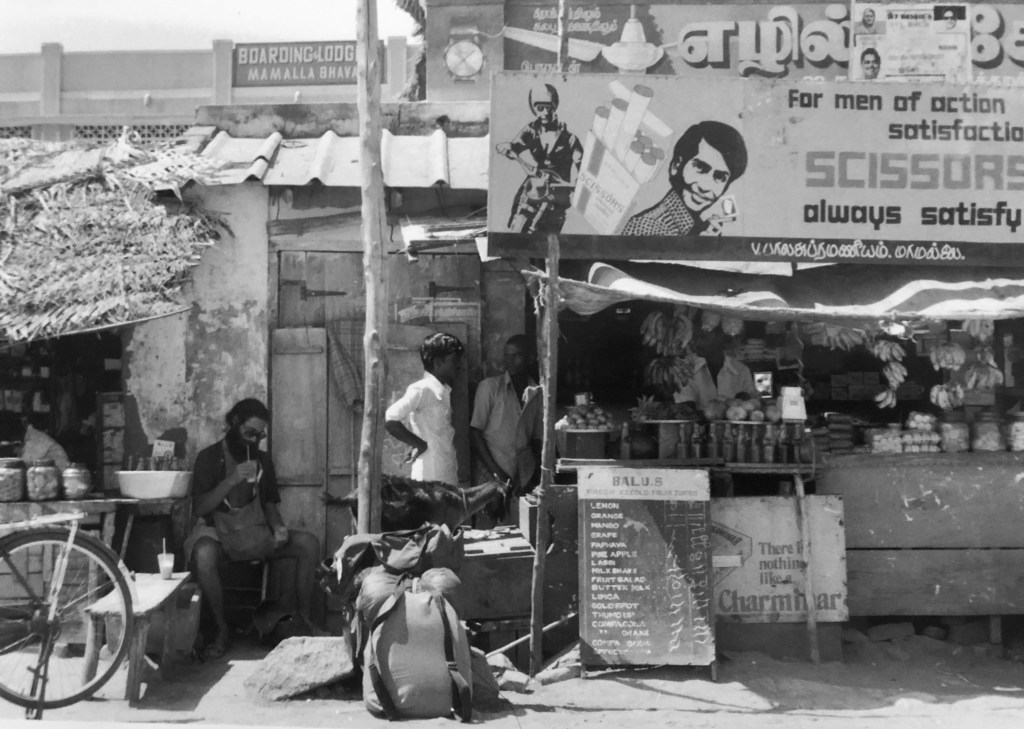

In the coastal village of Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu we stayed with a family who had a tiny two-room home and small subsistence farm. They generously gave up one of their rooms which had recently been coated in a fresh layer of cow dung, a practice that has been going for centuries for spiritual and practical reasons. The dung, once it has dried, does double duty repelling insects and evil spirits. The smell lingered slightly but was more pleasant than offensive. The cooking was done on an outside fire, wood was hard to come by so the fires and meals were small. Water was carried in jugs expertly balanced on the women’s and girl’s heads from the village well. The “toilet” was down a long path behind the house which led to the muddy shores of a shallow salt lake where one squatted. There were a few bushes but you daren’t go in, that was where the shit eating pigs rustled and grunted, jostling in anticipation of a warm breakfast.

We were treated with generosity and kindness by our host family, they made no special accommodation for us, they offered what they had. The youngest daughter took a shine to Phil and after school she loved to comb his long hair and beard. She attempted to do something with my short stringy locks, but was at a loss. Although I am sure whatever rupees we gave them for lodging were appreciated, they had so little space, food, and water to share in what appeared to be a cash free economy, providing for us had to be a burden. We didn’t stay long. I will forever be grateful to be welcomed into their home and will never forget them.

South Indian food is gorgeous, vibrant colours and deep flavours. Sit down meals, or thalis, are served on a banana leaf or a metal plate, rice or flat bread are surrounded by beautiful vegetarian curries and chutneys, scooped and eaten with the fingers of the right hand. Street food was almost always deep fried and delicious. Breakfasts were often a half papaya filled with thick yogurt and sliced bananas and drizzled with treacle. Tea is the national drink and there were carts on every street corner serving the sweet hot beverage from enormous steaming kettles. Meat and alcohol were not available and I thrived on the clean diet.

In Agra, under a full moon, we smoked opium fed to us through a complicated pipe while we reclined in a serene walled garden watched over by a goddess in the form of a long haired white cat. We later gazed upon the magnificent Taj Mahal from the back of a rickshaw, a bright white jewel reflecting the rays of the moon. We went back to the Taj the next day, sober, to explore it in daylight. I was unprepared to feel so moved by the beauty, detail, and the sheer size of this majestic and heartbreaking monument to love.

In Goa we rented an immense room in a dilapidated Victorian era mansion that was slowly being absorbed by the jungle. Our room had huge windows, a crazy high ceiling, and was furnished with two sleeping mats on the floor. Goa was, and probably still is, crawling with junkies and hedonists and seekers from all corners of the world. The restaurants served mushroom tea, banana pancakes, and hash brownies. I felt overdressed when I wore a bikini bottom on the picture perfect beach. It was beautiful and decadent and a little too cool for us. Leaving Goa, Phil went on to seek enlightenment from the mystic Bagwan Rashneesh at his ashram in Pune, and I continued north to Nepal.

Nepal

I was relieved to arrive in Pokhara which felt clean and fresh and uncrowded. I looked in at the local post office and was overjoyed to find a note from Michael reading “Last chance for sweet romance. Am in Kathmandu till April 6. Be there or be square. Love Mi.” Getting to Kathmandu was a challenge as there was a strike by bus drivers and only one mail bus a day was travelling the busy route. For the first time I fought like a local to gain a seat and ended up balancing precariously with the luggage on the roof for the long windy trip. It was all worth it when I found Michael, looking skinny but strong after a Himalayan trek, brushing his teeth at the outdoor sink at the wonderfully dilapidated Century Lodge.

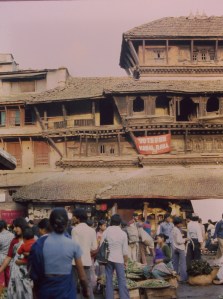

We had ten glorious days exploring the fascinating city, getting high, eating pie, wandering the temples and warrens of cobbled streets lined with crumbling ornate structures. Wealthy climbers and their entourage have been using Kathmandu to gather and prepare for their Himalayan conquests and to celebrate a safe return since the 60s. Luxury hotels and restaurants catering to international tastes had emerged serving Buffalo steak, fancy wines and cognacs, and more importantly, had introduced the local culinary scene to pie. All kinds of pie were displayed in grimy windows in front of soot filled hole in the wall shops, cherry, apple, coconut, custard, banana, or my fave, peanut butter chocolate.

Cannabis has been legal in Nepal since the 70s. It is widely used in Ayurvedic medicine and spiritual practices and of course recreationally by many travellers. On the infamous Freak Street there were plenty of “pie and chai” shops and a constant haze of hash smoke rising from chillums, the perfect combination of gustatory delights for the multinational stream of trekkers, hippies and stoners passing through. Some never left

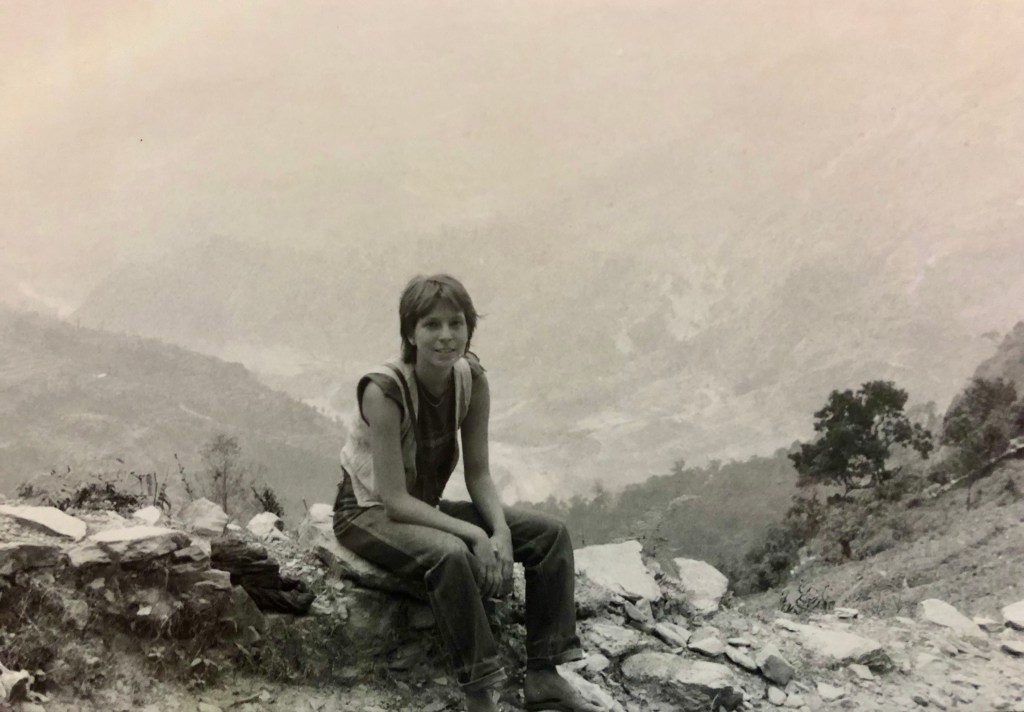

Michael made friends wherever he went

After Michael left I finished off my epic journey with a ten day solo trek in the foothills of the Annapurna Range, one of the easiest treks but still challenging for me. The Nepalese people I met along the way were open-hearted and kind, they walked by my side and shared smiles and whatever gruel type food was available. In the early mornings there were glimpses of the Himalaya range before the fog rolled in. I always found a roof of some sort to sleep under, often sharing with a goat or a chicken or two.

Finally, after four and a half months my $600 had run out. I cabled home for money for a plane ticket. The idea of returning to the concrete jungle of Toronto filled me with dread, so, much to my mother’s chagrin, I purchased a ticket to sunny Portugal where I had friends and a job waiting.

That wild winter was my initiation to real travelling. Michael was my catalyst and mentor, he was the one who inspired and challenged me to leave the comfort and mediocrity of middle-class life in Canada and explore the world, with no real goal except to seek out adventure and fun and the perfect beach. Of course along the way we learned so much about ourselves and the world around us, we widened our horizons in every direction. Everything seemed within reach and ripe for discovery. We learned about geography and history, about religions and languages, food, flora and fauna and how huge and small and dangerous and fragile our precious planet is. We learned how a smile, an offering, a kind gesture can surpass words. We witnessed poverty and cruelty always knowing we had a way out. I learned I had won the lottery in life and not to take my privilege for granted. I like to think I learned to be grateful, but I still need a reminder sometimes.

The next time I saw Phil was in Toronto. He had emerged from the ashram with a loving aura and a new name, Dipalmo, was wearing fire colours and a beatific smile.

Michael moved to New Orleans a few years later to start a life with his new love. Tragically he died soon after of AIDS at the tender age of 29, leaving so many broken hearts behind. I am sure that his bout of hepatitis in Asia left his liver compromised, his immune system weak, and shortened his life. At the time we laughed it off as another adventure, we thought we were invincible and that nothing could stop us.

Michael was my best friend for years. He was ridiculously funny, brilliantly creative, curious, gentle and kind. He made friends wherever he went. He made people laugh. He celebrated life. I still think about him often and am endlessly grateful for his friendship, the time I had with him and the many memories. I wish I believed.

Discover more from food by jude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wonderful recapture Jude!

LikeLike

Cherished memories. Thank you 🙏

LikeLike

This touched my heart Jude. Love you .Hugs!

LikeLike

Thank you Judy. Sending love.

LikeLike

Such a sweet picture at the top and a lovely essay.

I think about Lil’ Mi all the time too, Jude. And you and your sis.

LikeLike

Lovely to hear from you Gavin. Sending love.

LikeLike